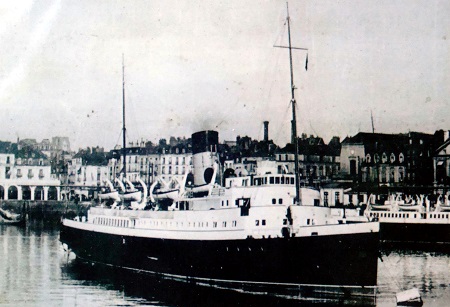

TS Brighton V before the war

Towards the end of May 1940 the Hospital Carrier (HC) Brighton V was ordered to Dieppe to evacuate British wounded. However, she was trapped within the Dieppe harbour basin, due to the failure of the lock gates. It is reputed that the gates were sabotaged by 'fifth columnists' sympathetic to the Nazi cause. The helpless vessel was then bombed and sunk during a subsequent air raid on the 24th May 1940. The crew split into three groups and on foot headed to Fecamp, Honfleur and Rouen respectively. Remarkably, all of the crew eventually returned safely to England.

Two views of HC Brighton V, sunk at her moorings in Dieppe Harbour

The story of the HC Paris is told by Mrs Helen Lewis, wife of the late Stephen Lewis of the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC).

"From 16th January 1940, to the day the Paris was sunk on the 2nd June 1940, my late husband Stephen Lewis, served aboard her along with many other brave souls. Like so many survivors of any war Stephen seldom spoke of his experiences, but over the years, I was able to build a picture of the ships exploits through those who served with him, along with the information he would divulge on occasions.

The Paris sailed into and out of Calais and Dieppe bringing back to the UK many wounded from both sides. During the May retreat, the Paris was the only ship to enter Calais, which she did on five occasions. The crew went ashore to search for wounded and then acted as stretcher bearers to bring them aboard to relative safety. On one of these occasions the CO was informed that a train carrying wounded had been abandoned by its French train driver half a mile from the station. Knowing that Steve had worked on the railway back home, the CO asked if he fancied getting the train down to the station [which he duly did]. From there the crew transported the wounded aboard the Paris.

On the 29th May the Paris evacuated 740 patients [from Dunkirk]. It was whilst helping the casualties aboard that Steve was saved from serious injury by his mouth organ which was mangled by a piece of shrapnel. The mouth organ was always carried in the long pocket located at the right thigh.

In the late afternoon of the 2nd June 1940 the Paris set off on her sixth trip into Dunkirk. It was at the start of the trip that the Bosun told Steve that they would not be coming back this time. When asked why, the Bosun replied

"Listen to the rigging whining and there are no sea birds following us."

How right the Bosun was proved to be. [At 7.15pm] A few miles from Dunkirk the Paris, painted white, with huge red crosses down her sides, was unmercifully bombed by German Stukas (so much for the Geneva Convention). The first bomb was a direct hit on the engine room killing one of the engineers (in fact it is believed that at least three bombs were dropped, all of which were near misses. However, the concussion of the explosions sprung the plates of the engine room and fractured the main steam pipe). Down came the Stukas again, machine guns blazing, this time hitting the fifteen year old cabin boy who was to die in Steve's arms. This experience was to haunt Steve for the rest of his life. (By this stage the ship was taking on a lot of water and beginning to develop a pronounced list, which resulted in distress flares being fired and the order to abandon ship being issued.)

The crew managed to get the life boats into the water but another bomb hit the boat containing the Queen Alexandra nurses, throwing them into the sea. They were quickly pulled aboard another life boat to safety. Sister Seeley was badly injured in the arm, so bad was the injury, that Steve's emergency dressing could barely cover the wound. The survivors of this barbaric attack on a defenceless hospital ship were eventually picked up by a tug boat [the Foremost 87] returning to England."

The Paris eventually sank around midnight, close to the West Buoy around 10 miles from the French coast. The relatively light casualties, 2 killed, were a direct result of the vessel being on her outward passage to Dunkirk, rather than being fully laden with wounded.

HC Paris in her hospital livery

Mention should also be made of the contribution of the Newhaven Lifeboat, the RNLB Cecil & Lilian Philpott. Her mission almost ended in disaster when she ran aground at Dunkirk and was left high and dry for 4 hours. Having been re-floated, she returned with 51 soldiers on the 3rd of June 1940. The lifeboat survived the war and ended her RNLI service in 1959. The vessel is now in private ownership and is officially recorded as one of the Dunkirk Little Ships.

RNLB Cecil and Lilian Philpott, the Newhaven Lifeboat

The photographs and much of the information included in this summary has been provided by the Local and Maritime Museum based in Newhaven. If you want to learn more about Newhaven's maritime history then please visit the Local and Maritime Museum at Paradise Park, Avis Road, Newhaven. Telephone number 01273 612530, website address http://www.newhavenmuseum.org.uk/