Pretty much every book covering the Dunkirk evacuation centres upon Dover's pivotal role in Operation Dynamo, often at the expense of the contributions made by other Kent and Sussex ports. This is understandable given that the planning and command structure was largely Dover-based, the bulk of the Royal Navy effort was centred on Dover and the fact that almost two-thirds of those evacuated passed through the port. Furthermore, the records of the events of the evacuation in Dover are better documented and photographed than those of the other ports involved. The following pages merely seek to provide a flavour of the events at Dover, rather than provide a detailed hour-by-hour summary, which would probably require a dedicated book or website of its own.

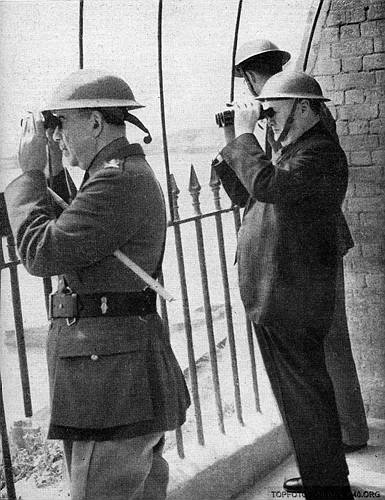

In August 1939, with war imminent, Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsey was appointed Vice-Admiral, Dover. His orders were to secure the Dover Straits and safeguard Allied shipping using this stretch of sea and he set up headquarters in the casemate tunnels beneath Dover Castle. For the period 26th May – 4th June 1940, these tunnels were the command centre for the greatest evacuation in military history.

Responding to the rapidly deteriorating military situation in France and Belgium, and under orders from the British Government and The Admiralty, Ramsey and his small team began to assemble an evacuation fleet to rescue the British Expeditionary Force from the port and coast surrounding Dunkirk. By this stage, the Aliens (Protected Areas) Order of the 29th March had already come into force in the Dover area, forbidding non-British nationals from entering, or remaining in the area without specific permission.

Fifteen passenger ships and ferries were initially assembled at Dover, together with other cargo vessels and coasters. Royal Navy destroyers, corvettes, minesweepers and naval trawlers based at Dover were reinforced by similar ships from commands at Portsmouth, the Thames Estuary and the east coast of England. In addition to the ships, crews, fuel, spare parts, rations, weapons, ammunition and medical supplies needed to be organised. For the landside part of the operation, special troop trains needed to be scheduled, hospitals and the emergency services placed on alert.

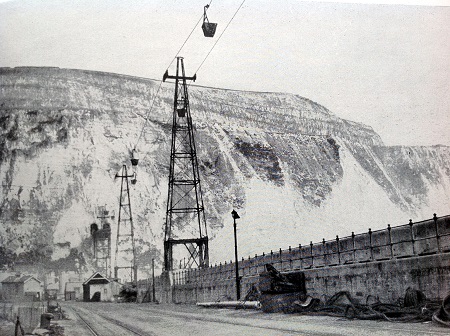

From the first days of the evacuation, the harbour was crowded with vessels unloading (often three abreast) then taking on more fuel and supplies for the next journey across to Dunkirk. Vessels of all shapes and sizes were tied up alongside the Eastern Arm, Admiralty Pier and Prince of Wales Pier, at whatever berths they could find.

Spirit and morale among the returning troops was generally high. Some units which had disembarked largely intact, fell in on the quayside and marched, as if on parade, to the station. However, as one coastal artillery officer recalled, some of the men who had lost contact with their units exhibited no such élan and a number were seen throwing their weapons into the sea. Morale on the Eastern Pier was not helped by the stacking of bodies, many of which were badly mutilated, just outside the gun battery which was located there.

The wounded were helped ashore. The more seriously wounded were placed on hospital trains, or evacuated to Buckland Hospital in Dover. Buckland Hospital admitted 4,500 seriously wounded soldiers and surgeons working day and night managed to save all but 50. Those with lighter wounds had them tended in the field dressing stations set up on the quayside.

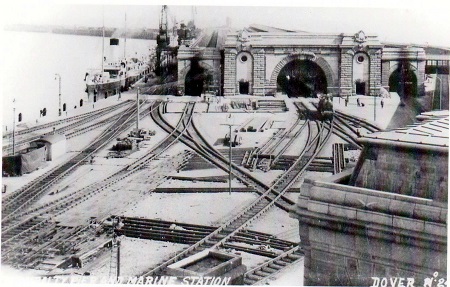

Troops were fed and put onto special troop trains to transport them to camps further inland for units to be re-organised and refitted. Southern Railway organised 327 of these 'Dunkirk Specials' to transport around 185,000 of the 200,000 allied troops landed at Dover. At the peak of the evacuation, a 'Dunkirk Special' left Dover Marine station every 20 minutes, each soldier reputedly being given a bun and a banana!

On the Eastern Arm, one of the coastal gun batteries set up a makeshift bar, courtesy of a generous local publican, and provided a free glass of beer for the returning troops.

Eastern Arm Dover.

Improvisation and rapid reaction to the changing dynamics of the evacuation were key to effective command of this complex operation. Time and again, well-laid plans were thrown into chaos by enemy action, but on each occasion, the planners in Dover and their liaison staff in Dunkirk found solutions to seemingly insurmountable problems. One of the problems they did not have to overcome was an actual German air attack on the Port of Dover itself. In retrospect, it is perhaps surprising that the Luftwaffe contented itself with the bombing and strafing of Dunkirk and its beaches and the evacuation fleet along the French and Belgian coasts. Had a heavy, surprise raid been mounted against Dover, the whole operation might have been thrown into chaos.

To read more about the Castle and Tunnels, please click here.

Back

Back