In 1940 Folkestone was a "Garrison Town" with a high-profile military presence. Identity cards were issued, key installations in the town were under guard and military checkpoints were established. Many locals had left Folkestone and the majority of the children were actually evacuated during Operation Dynamo itself on the 2nd June, 1940. Many businesses in the town were forced to close.

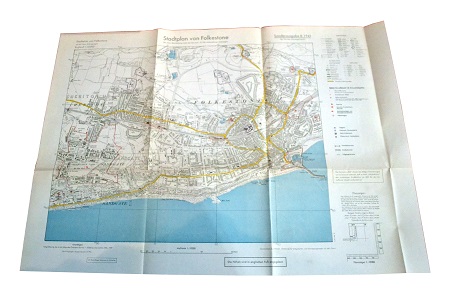

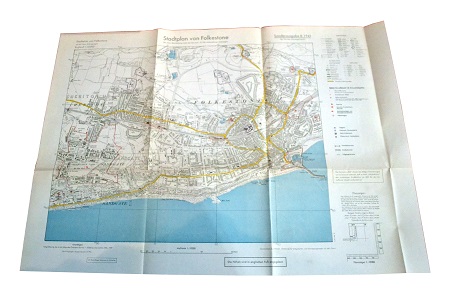

German Invasion Map of Folkestone.

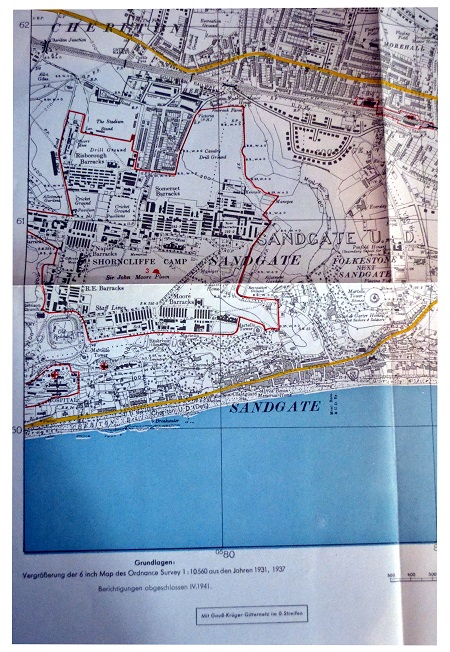

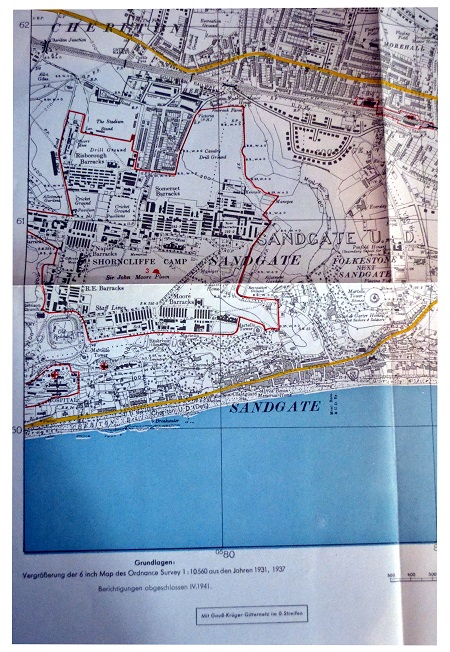

Close detail of the German Invasion Map of Folkestone.

Folkestone harbour was used by a number of cross-channel ferries, ferries and steam packets from elsewhere in the country, in addition to smaller craft. The harbour berths, designed for large vessels and the Folkestone Harbour railway station within the harbour complex, were in theory ideal for the large scale evacuation of troops. However, the spur line from the harbour was at a 1 in 30 gradient, which for heavily loaded trains could require three tank engines to get the train up the incline prior to attaching the main line locomotive.

Folkestone harbour and harbour railway station from the air.

Locals recall that every boat, big or small from the harbour went to assist the evacuation. Most of these boats never reported in to the Dover headquarters and the contribution that these "freelancers" made would never be officially recorded. They recall thousands being landed at the jetty and watching the trains cross over the arches by the harbour, full of exhausted soldiers. Many threw letters out of the windows asking residents to post them to their families. Many local people went down to Train Road, where the trains would pull up from the harbour at walking pace and showered the returning troops with gifts of cigarettes, chocolates and sweets.

German aerial reconnaissance photograph of Folkestone.

At Folkestone, morale among the crew of the London and North-East Railway steamer "Malines" began to crack. One of her fellow L&NER ships, the Prague, had been badly damaged earlier in the day and the crew were exhausted. A number appear to have been suffering from what we would now refer to as post-traumatic stress disorder, having been under intense bombardment during the evacuation of Rotterdam and two trips to Dunkirk. Her bunkers now full with coal, she was ordered to Dunkirk again on the evening of the 1st June. With the crew on the edge of revolt, the Captain refused to sail. Two other steamers, the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company (IoMSPCo) ships Ben-My-Chree and Tynwald, also refused to go. Like the Malines, these steamers had civilian crews and the IoMSPCo had already lost three vessels and a large number of crew in the Dunkirk operations. The Royal Navy officer in command at Folkestone had no alternative but to telephone Headquarters in Dover, requesting relief crews and armed guards. The IoMSPCo ships were eventually returned to operations with their crews stiffened with a Royal Navy cadre.

The L&NER steamer 'Malines'

Official figures state that 46 vessels called at Folkestone, landing 29,265 personnel. In turn, these troops were transported by rail on the 64 "Dunkirk special" trains that were allocated to Folkestone. Our museum is in possession of a large number of letters from veterans who landed at Folkestone.

German Invasion Map of Folkestone.

Close detail of the German Invasion Map of Folkestone.

Folkestone harbour was used by a number of cross-channel ferries, ferries and steam packets from elsewhere in the country, in addition to smaller craft. The harbour berths, designed for large vessels and the Folkestone Harbour railway station within the harbour complex, were in theory ideal for the large scale evacuation of troops. However, the spur line from the harbour was at a 1 in 30 gradient, which for heavily loaded trains could require three tank engines to get the train up the incline prior to attaching the main line locomotive.

Folkestone harbour and harbour railway station from the air.

Locals recall that every boat, big or small from the harbour went to assist the evacuation. Most of these boats never reported in to the Dover headquarters and the contribution that these "freelancers" made would never be officially recorded. They recall thousands being landed at the jetty and watching the trains cross over the arches by the harbour, full of exhausted soldiers. Many threw letters out of the windows asking residents to post them to their families. Many local people went down to Train Road, where the trains would pull up from the harbour at walking pace and showered the returning troops with gifts of cigarettes, chocolates and sweets.

German aerial reconnaissance photograph of Folkestone.

At Folkestone, morale among the crew of the London and North-East Railway steamer "Malines" began to crack. One of her fellow L&NER ships, the Prague, had been badly damaged earlier in the day and the crew were exhausted. A number appear to have been suffering from what we would now refer to as post-traumatic stress disorder, having been under intense bombardment during the evacuation of Rotterdam and two trips to Dunkirk. Her bunkers now full with coal, she was ordered to Dunkirk again on the evening of the 1st June. With the crew on the edge of revolt, the Captain refused to sail. Two other steamers, the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company (IoMSPCo) ships Ben-My-Chree and Tynwald, also refused to go. Like the Malines, these steamers had civilian crews and the IoMSPCo had already lost three vessels and a large number of crew in the Dunkirk operations. The Royal Navy officer in command at Folkestone had no alternative but to telephone Headquarters in Dover, requesting relief crews and armed guards. The IoMSPCo ships were eventually returned to operations with their crews stiffened with a Royal Navy cadre.

The L&NER steamer 'Malines'

Official figures state that 46 vessels called at Folkestone, landing 29,265 personnel. In turn, these troops were transported by rail on the 64 "Dunkirk special" trains that were allocated to Folkestone. Our museum is in possession of a large number of letters from veterans who landed at Folkestone.