HMS Apollo laying mines off Norway.

HMS Apollo laying mines off Norway.The use of naval mines goes back to the C16th and were first used in China, but were first used extensively in WW1. Mines are a relatively inexpensive weapon of war; they can be deployed by both ships and aircraft and can also be used in either an offensive or defensive role, depending on where and how they are deployed. In both world wars, all sides used extensive numbers of mines for defensive purposes, concentrated into areas referred to as minefields. Random laying of mines in strategic locations made their deployment one of an offensive nature. Naval mines are, like their land-based counterparts, indiscriminate and it is estimated that the cost of their use represents only about 10% of the cost of their removal. Because of the cost, danger, and inconvenience of their removal, even today some minefields laid in WW2 remain in place.

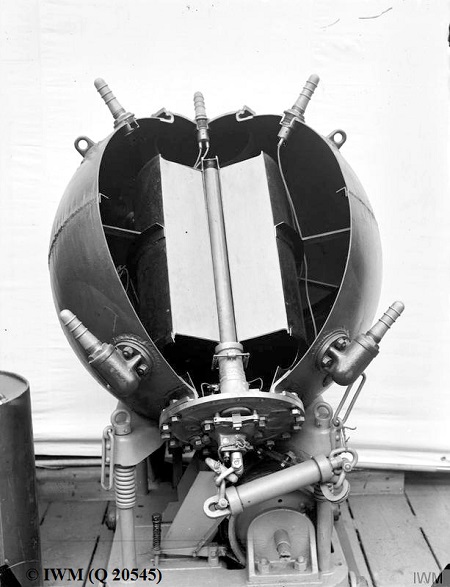

German mine probe.

German mine probe.

The Danish cargo liner 'Canada' sunk by a German mine in the North Sea off Holmpton, Yorkshire on the 3rd November 1939. Her crew of 64 were all rescued.

Typically, a mine consists of two main parts. The first is the trolley, which is used for manoeuvring the mine around prior to its deployment and doubles up as an anchor, to which the second part, the mine itself, is attached via a cable and released from when deployed. By WW2, there were several types of naval mines in use, although the examples here are of the basic contact type. Depending on the length of the cable, different kinds of targets can be aimed at. Mines were very often set to remain submerged and thus not alert shipping to their presence; those set further from the surface were deployed to prevent submarines from using the same area of the sea as surface ships.

British mine on trolley. Owned and on display at Lowestoft Maritime Museum, Suffolk.

German mine washed ashore near Dunkirk.

Both the Allies and the Axis forces issued their merchant and military navies with maps indicating the locations of the fixed defensive minefields and by and large, both sides knew the approximate location of each other's main minefields. The biggest problem was created by the mines becoming detached from their mooring anchors; due to their design, they would float free and could enter the shipping channels, presenting a random uncharted risk, equal in danger to those mines laid offensively by the enemy. Sectionalised British mine from WW1.

Sectionalised British mine from WW1.

The contact mine of WW2 was very similar in design to that used in WW1, as the principle of operation was as basic as it was effective. The mine consists of a steel barrel from which protrude small nodules (referred to as probes) made of lead and containing a glass phial, which once crushed by contact with a ship, released an acid which would burn through to an electrical contact and complete the circuit, detonating the mine. Contrary to the commonly-held view, the steel sphere was not crammed full of explosive, as a volume of air around the charge was required for the mine to float and only a relatively small charge was required. The size of the charge helped to keep the overall cost of the mine down and the damage was created by the shock wave which radiated from the explosion.

British mine. Owned and on display at The Royal Naval Patrol Service Museum Lowestoft, Suffolk.