Over the centuries, there have been numerous treaties based around the recognition of the borders of various countries. One of the oldest, and arguably one of the most important, was the Treaty of Verdun in August, 843, This treaty saw the Frankish Empire of Charlemagne being divided between his sons into what we would now begin to recognise as nation states. One of his sons was known as Louis the German, in itself an indication of the concept of a national identity emerging from the remains of empire. Prior to this treaty, identity was measured primarily at the level of family; before that of tribal and then to that of the empire. As wars flared and waned over the years, borders were redrawn and more treaties were agreed, some only to be become null and void in relatively short order; others would go on to stand the test of time. It was only natural that rulers would seek to consolidate what they already had, but also and more importantly, what they had now gained. Another major shift in this philosophy was the expansion of the concept of fortifications. These now served a larger purpose than that of the security of an individual (as in the case of a castle) or a community (as in the case of the walls surrounding towns and cities). The arrival of gunpowder and artillery in western European arsenals was also a major game changer, both in the style of construction and application of the actual sites being constructed. In the era of the castle, height was the main feature of any fortified work as it provided an advantage, which was a requirement for victory. Even before the arrival of effective artillery, the concept of multiple defensive works had already been brought into construction planning. However, once artillery begun to demonstrate its worth, it proved more important to extend the distance between attackers and their desired ultimate prize; furthermore, the height which had once offered the advantage to the defender now proved to be anything but advantageous.

Fast forwarding to 1815, we have one of the first examples of limitations placed on border fortifications, the Traité de Huningue. This prevented the construction and removal of existing fortifications due to their proximity to the border. In the wake of World War One, further limitations were placed on fortress construction where land borders existed. They were permissible only as purely defensive works, with any artillery mounted being restricted in potential range, or in other words, unable to be used as a basis for an offensive action. Artillery, in any case, performs best at distance, so the Maginot works are constructed 15km (9 miles) inside France where heavier artillery is involved. Forward of the main line are layers of lighter defences; once the main line was reached, the principle of defence in depth equally applied.

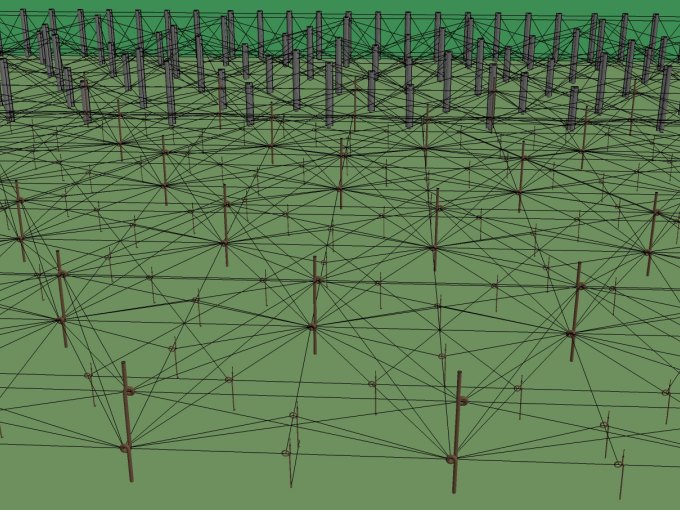

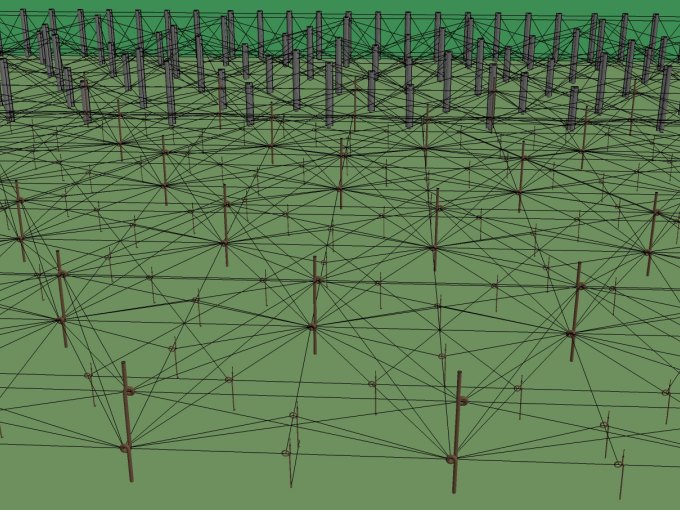

Main Barbed Wire Picket. Firstly, it is important to realise these are nothing like the mass-produced and relatively flimsy ones familiar to many from use in World War One. These were set into the ground encased in a concrete foundation, making a substantial barrier to a would-be attacker (see image below) These formed the anti-personnel aspect of the outer defence, with the row of rail tracks forming that of the ant-tank.

Piece of Barbed Wire. Genuine piece of barbed wire from the Maginot Line. Much of the wire was removed by the Germans during the years of occupation for re-use, either as intended or to be melted down and turned into munitions, Germany lacking any indigenous major iron ore seams. This work was undertaken by prisoners of war. When the French repaired the line in the years 1946-50, the wire was replaced. The site where we acquired this was never rewired, thus making this most certainly an example of original wire.

General Barbed Wire Picket. Only the main defensive line of wire was made up of the larger type (see above). In smaller installations this type was one of the many variants to which the wire was attached.

Fast forwarding to 1815, we have one of the first examples of limitations placed on border fortifications, the Traité de Huningue. This prevented the construction and removal of existing fortifications due to their proximity to the border. In the wake of World War One, further limitations were placed on fortress construction where land borders existed. They were permissible only as purely defensive works, with any artillery mounted being restricted in potential range, or in other words, unable to be used as a basis for an offensive action. Artillery, in any case, performs best at distance, so the Maginot works are constructed 15km (9 miles) inside France where heavier artillery is involved. Forward of the main line are layers of lighter defences; once the main line was reached, the principle of defence in depth equally applied.

Main Barbed Wire Picket. Firstly, it is important to realise these are nothing like the mass-produced and relatively flimsy ones familiar to many from use in World War One. These were set into the ground encased in a concrete foundation, making a substantial barrier to a would-be attacker (see image below) These formed the anti-personnel aspect of the outer defence, with the row of rail tracks forming that of the ant-tank.

Piece of Barbed Wire. Genuine piece of barbed wire from the Maginot Line. Much of the wire was removed by the Germans during the years of occupation for re-use, either as intended or to be melted down and turned into munitions, Germany lacking any indigenous major iron ore seams. This work was undertaken by prisoners of war. When the French repaired the line in the years 1946-50, the wire was replaced. The site where we acquired this was never rewired, thus making this most certainly an example of original wire.

General Barbed Wire Picket. Only the main defensive line of wire was made up of the larger type (see above). In smaller installations this type was one of the many variants to which the wire was attached.

The French Model 1936 anti-tank mine. These were used extensively in front of the forts of the Maginot Line. To learn more about this mine, click here.

Depending on how you arrived at this page please click on the options below:

To return to the Ouvrage Hatten, click here.

To return to the Ouvrage Hatten, click here.

To return to French Artillery, click here.