Balance of Global Military power on the eve of war in 1939.

To hear Neville Chamberlain address the nation click here.

France.

French Mobilisation 1939 scene at the Gare de L'est Paris.

France had a large conscript army with the potential to mobilise 6.7 million men from metropolitan France and its colonies. The French High Command calculated that in terms of land forces, they could raise 100 divisions plus 16 divisions of fortress troops. However, this ignored the fact that around 20 of these divisions would be required to man the Italian frontier and to meet its colonial commitments in North Africa and the Far East. The reality was that the French only had approximately 95 divisions to confront a German strength which had reached a level of around 116 divisions by mid-September, a number which was calculated to grow to 160 divisions plus by the beginning of 1940.

French General Mobilisation Order Poster from September 2nd 1939.This actual poster was displayed in the La rue Bayen, Paris.

France was not just disadvantaged by the discrepancy in manpower, but also in the highly variable quality of its army. It was only after 1935 that the conscription period was increased from one to two years. Hence, the bulk of reservists called up in 1939 had only received a year's training. Roughly one-third of the regiments were active units with regular officer and NCO cadres and with the bulk of the men being regulars.

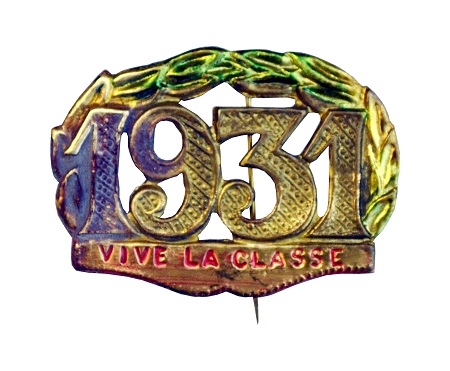

French Conscripts Class Badge.

The quality of these units was excellent. Upon mobilisation the army was strengthened by the creation of Series A and Series B regiments. Series A regiments were composed of reservists typically in their 20s and early 30s and a smaller cadre of regular officers and NCOs. Series B regiments were made up of the oldest military classes of men in their mid-30s and 40s and with very few regular officers. These units were of considerably inferior quality compared to the active units in terms of their training, equipment and morale. In many cases, Series B regiments performed better than their Series A counterparts, due, in all probability, to the presence of WW1 veterans with combat experience in their ranks. Many of the French units which held the Dunkirk perimeter were Series B or Regional Regiments.

French Mobilisation Poster recalling the former conscripts to arms. Dated 26th August 1939, the Number One indicates this to be from the very first batch of such posters, those with the troops of the highest priority to be recalled. As the day progressed higher and higher numbers were gradually issued.

France commenced mobilisation of reservists on the 26th August 1939 in response to the marked deterioration in Polish-German relations. General mobilisation followed at 0.00 hours on the 2nd September and war was declared the following day.

French Government poster issuing a notice to the general population that all private cars will be subject to requisition by the military.

The mobilisation was highly effective in generating the anticipated manpower required by the armed forces in France, although it took considerably more time to assimilate and integrate that manpower into the fighting units. However, the more serious problem was that the mobilisation was entirely indiscriminate. There was no effective legislation defining reserved occupations vital to the war effort and exempting those workers from being called up. As a result, there was an immediate dislocation in agricultural output and production from those industries vital to sustain France's war effort; it took months for these skilled technicians and workers to be identified and returned to their civilian roles. This meant that at a vital period of the military build-up, the French armed forces were short of promised new hardware and equipment, had insufficient ammunition and ordnance for many of their weapons and even faced shortages of basic equipment such as uniforms and boots. Hence, it can be seen that France was in no position to honour its agreement with Poland, i.e. that the French Army would start preparations for a major offensive within three days of general mobilisation.

Mobilisation booklet for French soldier 2nd class, Charles Dubourgnoux. Born in May 1911, resident of Clermont. In 1938 he was required to report to the Infantry Regiment Mobilisation Centre No. 132. In September, 1939 he is documented as reporting to the 208e Regiment d'Infanterie.

Military rail pass issued to Officer de Reserve Albert Perret, Service de Santé (French Army Medical Service), Montauban.

Member of The Artists Rifles on the platform of Sidcup Station in Kent with his Father, about to depart for war.

Unlike the major European nations in 1939, Great Britain did not have a large citizen army based on conscription. Instead, she had a comparatively small, well-trained regular army and a growing territorial army force of part-time soldiers. Her commitment to France was to provide four regular divisions as part of a British Expeditionary Force (BEF) within 33 days of French mobilisation and this was achieved. This complement had risen to five regular divisions by the end of 1939; between January and April 1940, a further five territorial divisions had arrived in France, providing the BEF with total manpower of 237,000 across its ten divisions.

British Civilian Radio.

Prior to the outbreak of war, conscription in a limited form had occurred. The Military Training Act of May 1939 specified the conscription of males between 20 and 22 years old, to undertake a six-month period of basic military training, prior to transfer to the Active Reserve. With the advent of war, the aforementioned act was superseded by the National Service (Armed Forces) Act of September 1939. This specified that all males between the ages of 18 and 41 years, not in a specified Reserved Occupation, were liable for conscription into the armed services.

National Service (Armed Forces) Act 1939 Certificate of Registration.

This example belonged to James Spence of St Nicholas Lodge, Kirkwick Avenue, Harpenden, Hertfordshire.

Belgium.

In 1936, Belgium had made a declaration of neutrality which had come as something of a blow to her former French and British allies. However, with the political tensions across Europe rising throughout the summer of 1939, Belgium began to mobilise its armed services from the 25th August. Initially, in the interests of maintaining its neutral stance, forces were deployed on both its eastern (German) and southern (French) borders. However, within weeks the redeployment to meet the more obvious German threat was achieved. Numerous alerts and false alarms of invasion followed throughout the winter of 1939-40.

Learning the lessons of previous exercises, the regular army was mobilised first with enlisted men following later. Restrictions were also placed on the opening hours of bars and premises serving alcohol. This was to ensure that the previous problems of drunkenness amongst mobilised conscripts was largely eliminated. Sixteen divisions totalling 600,000 men were mobilised initially. For a country the size of Belgium, this was an impressive feat and to put this into context, its army was three times the size of the BEF and had double the manpower of the Dutch Army. By May 1940, the army had grown to 18 divisions of infantry, two divisions of Chasseur Ardennais and two motorised cavalry divisions. However, fundamental weaknesses remained, notably the very small number of tanks available, limited anti-aircraft defence and air cover.

The Netherlands had been neutral in WW1 and hoped to remain so in any future conflict. There had been little investment in its armed services during the 1920s and 1930s and its army was both poorly- equipped and -trained as a result. The rates of conscription had been very low and up until 1938, those few that were conscripted received only 24 weeks of basic infantry training. No large-scale field exercises by the army took place between 1932 and 1936 and the professional officer cadre only numbered around 1,200. There was a complete absence of tanks and what aircraft it possessed were largely outdated by the start of WW2.

Notwithstanding the obvious weakness of its armed forces, the Dutch felt compelled to mobilise 100,000 men in April 1939, post the German invasion of Czechoslovakia. With the Polish crisis rapidly developing, on the 24th August 1939, it moved to a full mobilisation of nine divisions and 280,000 men.

To view a set of French mobilisation paperwork, click here.

For pictures of a French Transport Corps uniform click here.

For a gallery of a set of mobilisation posters click here.

To view a Livret Militaire which belonged to Sergeant Christian Dyckhoff of the Belgian Army, please click here.

To view a British National Registration ID card, please click here.

To view a French Infantry uniform, please click here.

To view a French Officers luggage trunk, please click here.

To return to the main museum, click here.